Iraq After Invasion: How a Country Lost Time

From Oil Trusteeship and Strongman Politics to Two Decades of Lost Sovereignty

All of Iraq’s oil export revenues flew through an account held at the U.S. Federal Reserve. To access these funds, Iraq’s Ministry of Finance must submit requests to the U.S. Treasury, which had the authority to approve or deny the transfers.

The world is consisted of many countries, each having very different lifestyle. If one never goes around, one may never realise how a single clause in a historical agreement can continue to shape everyday reality decades later.

At the beginning of the new year, after a week of food and comfort in Asia, I set out for Iraq.

The Mesopotamian plain was one of the earliest cradles of human civilisation—perhaps the earliest. Thousands of years ago, written civilisation already existed here. Before Jesus was born, emperors in this land were already shaping legends.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, one of the most prominent strongmen in modern Middle Eastern history, the United States effectively took over Iraq, while Iran came to dominate much of its economic life. “Defeat” does not mean the dramatic downfall of a leader but decades of loss for tens of millions of people.

Today’s Iraq stands on a booming oil economy, and many parts of the country appear prosperous. Yet its oil revenues are under U.S. oversight; its politics shaped by both Washington and Tehran. As global energy structures shift and hegemonic power changes course, an oil-dependent economy may one day collapse. Ordinary Iraqi neither want nor are able to look that far ahead - especially in the strongholds of Shi’a, where religious authority remains deeply entrenched.

I asked my guide, “Do you think Iraq is a colony of the United States and Iran?”

He paused for a moment and said, “Maybe.”

Perhaps “colonialism” is a too harsh word. Iraq is, rather, a sovereign country that lost the ability to determine its own fate, much like many states today under a world shaped by great-power rivalry.

At a time when the U.S. captured Maduro and swung its stick to Iran, it feels like the right time to tell the Iraqi story.

Choosing the Lesser Evil: Story between Saddam Hussein and the United States

At the beginning, Saddam Hussein and Washington were on surprisingly “sweet” terms. Washington’s stance toward Saddam was never truly about the man himself, but rather about how Iraq fit into America’s broader Middle Eastern strategy at different moments in time.

For readers in China, this pattern should feel familiar. The early “honeymoon” followed by a steady deterioration closely resembles America’s cooling attitudes toward ROC’s Chiang Kai-shek and Song Meilin. U.S. foreign policy has always followed its own regional positioning and definition over allies and enemies. For example, during the Cold War, the enemy was the Soviet Union; in Iraq’s case, it was Iran.

In the 1970s, both Iraq and Iran were relatively well-to-do societies. Compared with China at the time, some of their citizens already could board airplanes and women dressed according to global fashion trends.

Under the Cold War framework, containing Soviet expansion was America’s top priority worldwide. This calculus shifted dramatically in 1979, when Iran’s Islamic Revolution overthrew the U.S.-backed Shah. Iran transformed overnight from an American-supported authoritarian ally into a fiercely anti-American, anti-Israel theocratic state.

The storming of the U.S. embassy in Tehran - later vividly Hollywoodised in the film Argo - was the micro-level manifestation of this macro-level geopolitical rupture. From that point on, America’s Middle East strategy became clear: to prevent Iran from exporting its Islamic Revolution ideology and secure Gulf stability (for the US).

On the East, the U.S. was willing to support another rising power to contain the Soviets, an episode that reshaped global power dynamics; tho the story will be saved for another time.

In 1980, Saddam seized what he believed was a strategic opportunity. Iran’s new regime was still consolidating power, and Iraq launched the Iran–Iraq War. The United States disliked neither Khomeini’s ideological rigidity nor Saddam’s arrogance. But when forced to choose between two evils, Washington chose the lesser one on the appearance. Compared to the black-robed revolutionary cleric, the then middle-aged Saddam appeared more malleable.

Between 1980 and 1988, the United States provided Iraq with extensive support, including intelligence sharing, satellite imagery of Iranian troop deployments, diplomatic and economic normalisation, and exports of dual-use technologies. In 1982, Iraq was removed from the U.S. list of state sponsors of terrorism. Between 1985 and 1989, American companies exported computers, chemical equipment, and biological research materials to Iraq, some of which were later suspected to have been used in chemical weapons programs.

In 1988, Saddam’s regime carried out a chemical weapons attack on the Kurdish town of Halabja, killing approximately 5,000 civilians within hours - one of the worst chemical attacks against a civilian population since World War II. The United States chose to tolerate it.

For Washington, the priority was containing Iran, not punishing Iraq.

The Iran–Iraq War ended in 1988 after years of stalemate. No one truly won. Iraq suffered an estimated 200,000–300,000 military and civilian deaths. Direct economic losses mounted to $80–100 billion, and a ballooning national debt exceeding $80 billion, much of it owed to Gulf states. Its oil infrastructure was severely damaged, leaving the postwar economy extremely fragile.

Iran’s losses carried even deeper into generational consequences. Estimated deaths range from 300,000 to 500,000, with over half a million wounded or disabled. The war consumed an entire generation of post-revolutionary young men and inflicted economic losses exceeding $500 billion when long-term opportunity costs are included.

After the war, Iran reframed the conflict as a “Sacred Defense,” embedding it into a broader narrative of resistance against oppression, hegemony, and foreign intervention. Iraq, by contrast, emerged with no clear victory and a hollowed-out state, setting the structural stage for its later invasion of Kuwait and eventual collapse.

By 1990, Iraq was financially exhausted. Like Germany after World War I, it stumbled from one war into another. In August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, marking the irreversible breakdown of U.S.–Iraq relations.

Our contemporary global diplomacy has a red line: the United States may tolerate you fighting its enemies within its system, but it will not allow you to grow powerful enough to challenge the system itself.

Energy structures are power structures. Threatening the global oil order is tantamount to threatening the U.S.-led international system. Iraqi troops advancing into Kuwait came within dozens of kilometers of Saudi Arabia’s border, which directly endangered America’s most important Middle Eastern ally. Washington had little choice but to act. The result was the U.S.-led coalition of 34 countries and the 1991 Gulf War. Operation Desert Storm swiftly defeated Iraq.

Saddam was not removed. Much like how the U.S. once left Chiang Kai-shek a fallback, Washington understood that in the Middle East, the absence of a strongman often leads to warlordism and fragmentation. A disintegrated Iraq would empower Iran and destabilise the region, threatening both Israel and Saudi Arabia. Saddam remained in power but under punishment.

Within the U.S.-dominated liberal economic order, long-term sanctions are a devastating weapon. They slowly grind down a nation’s vitality until collapse comes from within.

From 1991 to 2003, UN sanctions, driven largely by the U.S., slashed Iraq’s GDP by over 60%. Throughout the 1990s, child malnutrition exceeded 25%, and the healthcare system nearly collapsed. However, you are dealing with Saddam Hussein, the famed or notorious Middle Eastern personality. I previously wrote that his government exploited the UN’s Oil-for-Food programme to circumvent sanctions and extract billions of dollars. Due to conflict of interest, I will not elaborate further here; interested readers may search for it yourself.

Over time, the U.S. employed a familiar strategy: “containment without overthrow, punishment without resolution.” Saddam’s image was gradually recast from a secular strongman opposing Iran to a destabilising force and a “potential WMD threat.”

After 9/11, American elites lost patience with disruptive strongmen. For the first time in a century, the U.S., a country long sheltered by oceans, realised its homeland was not invulnerable. Iraq was already demonised for a decade and then became the obvious target. In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq.

In hindsight, the invasion was a catastrophic miscalculation. The three justifications: WMDs, terrorism, and “liberating the Iraqi people”, collapsed under scrutiny. The war turned the UN into a global farce, cost the U.S. over $2 trillion, and shattered the moral credibility of the liberal democratic “beacon”.

The collapse of authoritarian control created a power vacuum, from which ISIS emerged and ravaged the region for the next decade. At the systemic level, America’s self-inflicted blow also created narrative space for China’s alternative vision of global order.

Postwar Iraq: How Much Did the United States Really “Take”?

Passing through Tahrir Square, my guide and driver pointed to a stone pedestal and said, “That used to be Saddam’s statue.”

The removal of Saddam Hussein’s statue was one of the defining images of the early 2000s. It symbolised the end of a strongman era in Iraq but also the end of an era in which Iraq was able to govern itself.

By conservative estimates, the United States incurred approximately $2 trillion in direct costs from the Iraq War, including combat operations and long-term military deployment. More moderate estimates factoring in veterans’ healthcare, disability benefits, and postwar obligations place the figure closer to $2–3 trillion. Some broader calculations, including long-term interest payments and opportunity costs, push the total to $4–6 trillion over several decades.

For Iraq, the cost was at least a decade of turmoil. After 2000, waves of displacement followed. Millions fled to Europe, Syria, Jordan, and beyond. The power vacuum enabled the rise of ISIS, turning northern Iraq into a powder keg. I still remember attending events at Chatham House in London around 2014, where Yazidi leaders pleaded with the international community to recognise the genocide in Kurdistan and called for united defense against ISIS.

For this trip, I deliberately avoided Mosul. I could not bring myself to revisit land where the missing limbs of children from 10 years ago would still be found.

Iraqis are rebuilding their country. But a whole era has disappeared. From a purely economic perspective, did the United States ever “break even” on the Iraq War?

Saddam Hussein, ruling over one of the world’s major oil states, was undeniably wealthy. He reportedly maintained 22 palaces across Iraq, and his family’s assets were estimated at $20–100 billion. When U.S. forces entered Baghdad, they discovered approximately $650 million to $1 billion in cash and large quantities of gold stored at the Iraqi Central Bank. Since the bank effectively answered to Saddam alone, many Iraqis believed these assets were personal holdings of the Hussein family.

Officially, these funds were later used for government operations and reconstruction. In practice, their final disposition remains opaque.

The opening statement of this article captured U.S. supervision of Iraq’s oil revenue, which was a temporary postwar arrangement mainly between 2003 and 2010. In 2003, the UN passed UNSCR 1483, establishing the Development Fund for Iraq (DFI). Under this framework, Iraq’s oil export revenues were temporarily placed under international trusteeship, which was effectively under U.S. oversight, for postwar governance and reconstruction. The language used was “custodianship.”

In parallel, the U.S. froze significant Iraqi state assets abroad and confiscated portions of the Saddam family’s wealth though much of it had already been transferred out of reach before the war or has never been fully accounted for.

What fueled public anger was not only these arrangements, but systemic corruption during the reconstruction decade: fraudulent contracts, chaotic U.S. cash management, local patronage networks, black markets, and armed groups siphoning funds. These patterns echoed earlier scandals such as the UN’s Oil-for-Food program.

My guide said bluntly, “Ninety-nine percent of our oil income goes to the United States.”

Academically speaking, this is inaccurate. Foreign oil companies in Iraq largely operate under Technical Service Contracts (TSCs), which typically account for only 5–10% of total oil revenue. In theory, 85–90% of oil income belongs to the Iraqi state.

However, for decades, that revenue has failed to translate into everyday life. Although living standards have improved somewhat in recent years, corruption remains endemic, government efficiency is low, and basic services such as electricity, water, employment are still inadequate.

The post-2003 sovereignty shock continues to shape Iraqi society. A country rich in oil was invaded, stripped of autonomy, and left unable to convert its resources into public welfare. Under such conditions, public trust in government collapses.

In contrast, Chinese companies operating in Iraq are often viewed more favorably by locals. Unlike Western firms that rely heavily on expatriate management, Chinese companies tend to hire locally, accept lower short-term returns, and operate on longer time horizons. To many Iraqis, this model feels more tangible and trustworthy.

As fellow Global South actors, China carries no imperial legacy in the region. Its reputation focused on infrastructure, trade, and development rather than overt political control so it was often compared favorably with that of Western powers.

Looking back over the past two decades, asking whether the United States “recouped” its investment in Iraq feels almost cruel. What truly vanished was not a line item on a balance sheet, but an era.

What fell in Tahrir Square was not only Saddam’s statue, but a brutal yet predictable order. What followed was not a clearer or more humane system but prolonged uncertainty.

On paper, Iraq’s oil wealth still belongs to the state. In reality, it has rarely materialised into electricity, water, jobs, or dignity. Naturally, in everyday narratives, people conclude that the money must have been “taken.” Otherwise, life would not look like this.

Perhaps what Iraq truly lost was never its oil but its time.

Ali’s Tombstone: The Tragic End of a Shi’a Hero

Longtime readers know that I share a deep and complicated history with Iran. My first steps into the Middle East began with a love story in Iran in the past. That chapter has since closed. Eight years later, I have carved out my own path from those beginnings.

In Iran, across countless days and nights, Ali is an inescapable name. Much like Qin Shi Huang in Chinese history, Ali’s story forms the tragic core of Iran’s national psyche.

Once, the Persian Empire stood among the great powers of history, which is no less formidable than Rome or modern-day America. Across Eurasia, many of the ancient ruins I’ve encountered trace the far reaches of Roman frontiers or Persian expansion. I cannot condense the tremendous Persian story into one page; so here, let’s begin with the Arab conquests.

After years of campaigns, the Prophet passed away without formally appointing a successor, leaving behind one of history’s most consequential ambiguities.

In 632 CE, the leading figures in Medina selected Abu Bakr, the Prophet’s father-in-law, as the first caliph. Ali, Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, objected. He argued that the Prophet had earlier declared, “Whoever takes me as his mawla, Ali is his mawla” - a statement whose interpretation remains contested to this day.

Ali was married to Fatima, one of the Prophet’s dearest daughters. Though relatively young, he was widely respected for his virtue, scholarship, and military merit by most accounts almost indisputable. I would say he could be considered the glam boy of his day. While he initially abstained from Abu Bakr’s selection, he later pledged allegiance to him.

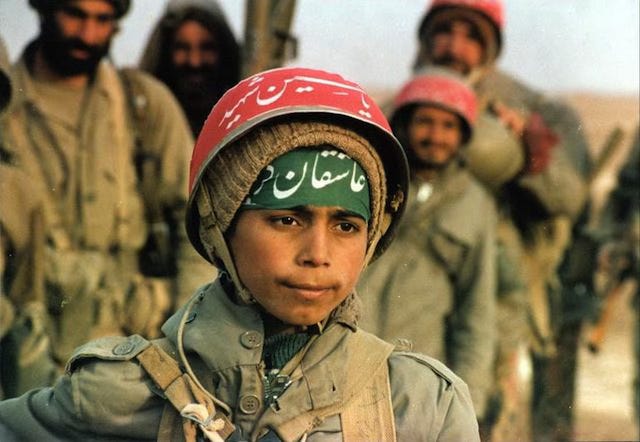

By the time Ali became the fourth caliph, the empire unfortunately had already fractured. Civil war (fitna), followed. In 661, Ali was assassinated in the mosque of Kufa, in what is now Iraq. Years later in Karbala, his son Husayn, accompanied by only around seventy followers that included women and children was surrounded by Umayyad forces numbering in the thousands. The men refused to surrender and were killed to the last.

Iran, conquered by Muslim rule, internalised this same tragic heroism.

In Sunni narratives, history is written by the victors. In Shi’a tradition, however, righteousness lies with the dispossessed with those who are marginalised, slaughtered, yet remain defiant. This is the moral grammar of Shi’ism.

In China, although mainstream narratives often celebrate imperial zeniths, we still honour figures like Xiang Yu, or commemorate tragedies such as the Battle of Yashan, which are stories of individuals resisting overwhelming odds. Because justice is rarely black and white; defeated heroes are not villains, and victors are not always virtuous.

Every year, in Shi’a-majority regions, Ashura commemorates the death of Husayn. The ethos of “knowing defeat is certain, yet choosing to die anyway” is not unique to Shi’ism. Long before Islam, Persian culture carried similar heroic motifs.

In The Shahnameh (Book of Kings), the Persian national epic, heroes often die young. Their ambitions unfulfilled. Dynasties rise and fall but their moral nobility triumphs over fate or power structures. It is not an epic of conquest, but of how dignity survives defeat as a civilization narrating itself after empire has collapsed.

In modern times, this tragic ethos has been translated into political language, sustaining Iran’s anti-hegemonic discourse against Israel, the United States, and external domination. Over the past thirty years, America’s maximum pressure strategy has failed to crush Iran entirely. The reason lies not only in geopolitics or institutional resilience, but in a national psychology nourished by tragedy. It’s the everlasting Zoroastrian sacred fire: slow-burning, but difficult to extinguish.

In Najaf, I was determined to see Ali’s final resting place.

Under the glittering dome, Ali’s coffin lies quietly. Women in black chadors rushed forward, one after another, racing to touch the shrine. Overwhelmed by the crowd, I stood at a distance and took a selfie. Some women wept softly, whispering their sorrows to Ali. Others recited the Qur’an, believing the sanctity of the place would amplify their prayers. Many, myself included, I would say were merely bored beholders with cameras in hand, no different from tourists in a park.

Iraq is often called the land of a thousand shrines. Many mosques are breathtakingly opulent, almost blinding. Yet poor management leaves them overcrowded, making the pilgrimage experience underwhelming (or overwhelming for some). I’m personally influenced more by Vedic and Buddhist thought, so I found myself conspicuous - a tall, red-haired Asian woman in a sea of black chadors. I withdrew from the crowd.

That evening, I spoke with an American friend and my Chinese family about my “pilgrimage”. My family looked at my photos of veiled women and called them “ignorant masses.” Islam, of course, is layered with complexity, and I have no desire to pass sweeping labels. My writing seeks to help readers better understand history and society and the readers should hold their own judgement.

Still, I believe that when dealing with “fools,” one must sometimes use “foolish” methods much like Chen Jinnan’s dealings with the Heaven and Earth Society.

The relationship between self and the divine is a lifelong question. It does not require institutional religion to mediate it. Once spiritual inquiry becomes socialised, it merely reflects power structures and their allocation. I’ve visited countless churches, temples, and shrines; believers abound, true seekers are rare. What I see is desire. People pray for wealth, power, love. The motif is similar to those past wars waged by emperors; in the end, it’s about bills and bitches.

The American friend once joked that someone as bored as me could probably rally followers, if I “give them what they want”. I said: I don’t need to give them what they want; only “what they think they want”.

Just nonsense talk. Readers may laugh and move on.

My Iraq trip ended earlier than planned. Despite years of strength training, my health faltered soon after arrival. This is nothing new. By conventional standards, I already possess much: youth, appearance, wealth, status, the freedom to move across cultures and political worlds, and an intensely perceptive mind. I no longer dare to wish for a bull-like body, or even for the perfect lover many readers are keen on gossiping.

Dissatisfactions are the constant in life. Suffering comes from wanting too much. If one could truly accept the moment, what necessities would there be for one to travel thousands of miles and venerate a shrine? Even saints could not have everything. How much less so, you and I?